First, I want to think my friend Megan for gifting this book to me. And I’m going to regift it as suggested.

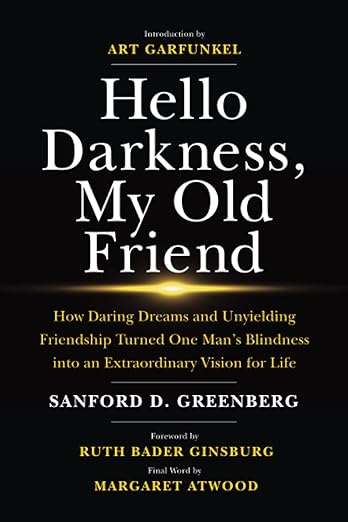

You’re not alone if the name Sanford Greenberg is new to you. After reading his memoir, I suggest taking the time to get to know him.

His life is triumphant in numerous ways, most notably the journey of taking the tragedy of going blind and living life to the fullest in spite of it. How he accomplished finishing college and going after other degrees is one thing. But continuing to dream big and go hard in all areas is equally inspiring.

Knowing I’m regifting the book, I didn’t do any highlighting. Out of many elaborative thoughts and quotes, I’d like to share just one from chapter 14, “The Start of Something Big.”

I was bitten by some kind of bug. Once someone gets his or her resolve up and running, and gets it focused in a direction, it is hard to put on the brakes. In a word, there is momentum. Also, aggressive work habits form. For us blind people, it is especially hard to hold back because we are always concerned about security. Like those who survived and prospered long after the Great Depression but could never shake the habit of stockpiling food and cash for a rainy day, we never feel comfortable, in our guts, about sitting back and saying ‘Okay, that’s it. I’ve done enough.’

Sitting back. It seems to be an art form of sorts. Or at least some form of discipline that some do naturally and others work hard to pursue.

Security. It seems to be more and more pursued yet less and less attained.

Greenberg’s journey of learning to sit back and where to find security led him to this conclusion: “The only worthwhile things in the world are people and ideas.” These drove him to an extraordinary life that may have only been possible due to overcoming tragedy, striving for the light.

I’m richer for having read Sanford Greenberg’s memoir. I’m glad we met.

If it’s doubtful you’ll read it, enrich yourself by watching this video about his lifelong friendship with Art Garfunkel.